Native Plants for our Gardens:

Two magnificent new books explain which ones to choose and how to grow them

We often hear of the importance of using native plants in our gardens.

First and foremost, native plants are extremely beneficial for the wider environment. In addition, since they are adapted to our climate, they should be easy to grow. And finally they help us create gardens with that elusive feeling of ‘belonging’ in the wider landscape.

But a little thought also tells us that casually introducing a profusion of wild plants into a garden is not necessarily that straightforward! For instance, since most native plants are tough enough to endure competition in the wild, some species may be much too aggressive for most gardeners. Conversely some species only grow in very unique habitats (such as on limestone bluffs) and are unlikely to survive in any garden that cannot replicate their special environments. And finally, it takes knowledge and skill to harmoniously integrate wild flowers among more highly bred companions.

But there are hundreds of native plants that WILL work beautifully in a garden setting. To help us get to know which ones to use and how to grow them, two great new books describing the best native plants for use in the garden have just arrived on the scene.

Both books are incredibly informative and beautifully illustrated They will help you right now as you plan your garden for the coming year; and they would also make great additions to your long-term collection of reference books. Let’s look at each in turn:

‘Native Plants for New England Gardens’ by Mark Richardson and Dan Jaffe, published by Globe Pequot

The authors have both worked for decades at The New England Wildflower Society’s legendary ‘Garden in the Woods’, thus accumulating a wealth of practical experience on actually growing native plants to their best advantage in a garden setting.

The authors have both worked for decades at The New England Wildflower Society’s legendary ‘Garden in the Woods’, thus accumulating a wealth of practical experience on actually growing native plants to their best advantage in a garden setting.

This book has four sections, each arranged alphabetically by genus:

- Herbaceous perennials that produce colorful flowers each season and then die back to the ground in winter;

- Threes and shrubs with woody skeletons that remain above ground in the winter, adding to the winter garden scene;

- Ferns, grasses and sedges—a mix of plant types which collectively add delicate textures to our garden compositions and also often make great ground-covers;

- And finally a small group of vines and other climbing plants.

As the title indicates, this book covers plants that grow naturally at least somewhere in New England, which includes areas where the winters may be quite a bit warmer than those we experience in Vermont. Much of Vermont is rated as Zone 4 (meaning that, once in a while on the coldest nights, the temperature may drop as low as minus 20 to minus degrees Fahrenheit) whereas in parts of Massachusetts it is unlikely to go below 0 degrees Fahrenheit.

Thus a few of the plants listed in this book will not be hardy enough to survive our Vermont winters. Check the hardiness zone where you live (http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/) and then just be careful to choose plants that are rated for your zone or lower.

Interested in a particular plant type? Plants are organized by Latin name or genus, so most of us will use the index of common names to get to the right page.

For each genus the authors describe all the species they consider truly garden-worthy, how they can best be used and their environmental benefit. And equally important, they also note other species of that genus to avoid! In addition, for at least one plant in each genus, they provide a lovely photograph taken at Garden in the Woods.

Every fall three lovely natives light up this corner of my garden: New England Asters, Black Eyed Susans backed by a group of Winterberries

The authors have a delightfully chatty style which tells me they are totally familiar with the practicalities of actually growing all these plants successfully and of using them to their best advantage within an overall garden design.

And, even though the book is organized alphabetically, this chatty style also makes it thoroughly enjoyable to read from cover to cover. In doing this, I become acquainted with some lovely plants that I had never even considered for my own garden. For instance the Wreath Goldenrod (Solidago caesia) and the Downy Goldenrod (S. puberula) are both well-behaved diminutive plants that bloom at the same time as New England Asters—and they are completely different from their tall thuggish cousin, the Canada Goldenrod (S. canadensis) which always seems to arrive in my flower beds uninvited and, given a chance, will colonize an entire meadow.

And finally, they also offer useful lists of plants for specific conditions—such as sunny, shady, boggy or dry; and for various needs—to attract pollinators, songbirds or wildlife and for fall color or winter interest.

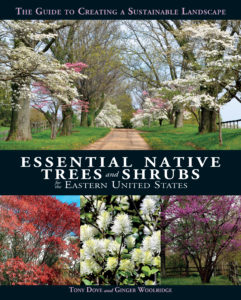

‘Essential Native Trees and Shrubs for the Eastern United States’ by Tony Dove and Ginger Woolridge, published by Charlesbridge

This book is readable, informative, extensively cross-referenced and, of course, beautiful illustrated. Together the authors have years of horticultural experience, one as a public garden manager and the other as a landscape architect. And they too have drawn on their combined practical knowledge to select just those native woody plants that they recommend for using in a garden.

This book is readable, informative, extensively cross-referenced and, of course, beautiful illustrated. Together the authors have years of horticultural experience, one as a public garden manager and the other as a landscape architect. And they too have drawn on their combined practical knowledge to select just those native woody plants that they recommend for using in a garden.

The book is organized into three parts for easy access and detailed reference:

Part 1: Site Conditions and Plant Attributes offers forty individual lists that take you directly to the plants listed in Part 2.

Start here if you are looking for trees or shrubs with particular attributes, for instance those with showy flowers or evergreen leaves, or for plants that will tolerate shade, wind or salt, or even deter deer. There are also lists of shrubs and trees that will mature at different heights and many others.

Part 2: Primary Trees and Shrubs, organized alphabetically by genus, is the core of the book.

Here you will find a detailed and easy-to-understand description of each featured plant, including its landscape attributes, seasons of interest, size and form, texture and color, cultural information, wildlife benefits and recommended companion plants, as well as favorite cultivars.

In addition there are several photographs showing the plant during different seasons, plus two invaluable charts:

- A drawing showing the plant’s height and shape at maturity alongside a human figure for comparison;

- The range of hardiness zones which the plant can accommodate plus its soil acidity and moisture requirements.

And, while the geographical scope of this book covers a relatively large area— east of the Appalachians from Canada to the Carolinas—do not let this deter you. A quick look at the hardiness zone chart for each plant will tell you whether it is viable for growing in Vermont.

Part 3: Secondary Plants, provides a brief description of additional trees or shrubs that the authors feel might work is certain situations, but also that had limitations for many gardens.

Thinking outside the box

Back in 2007 Douglas W. Tallamy, Professor of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, published his ground-breaking book ‘Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants’.

Here he summarized a considerable body of academic research demonstrating how native plants create that all-important bottom layer of the food-web in the ecosystem. This is the layer that is the food source for many kinds of insects, including pollinators and butterflies.

And furthermore, he points out that most insects are specialists; i.e. they require particular plant species—typically native—for successfully reproduction. Thus a diverse mix of native plants is essential to support a wide variety of insects, including butterflies and pollinators. In turn some of these will feed the birds and other wildlife that we treasure.

We all know that the landscape does not stop at the property boundary; even the smallest garden is truly part of the wider continuous ecosystem. So, as gardeners, it behooves us to look for ways to create gardens that, in addition to being beautiful and giving pleasure to people, will also make a positive impact on this wider environment.

Incorporating a variety of native plants in your planting designs is a great way to create a beautiful wildlife-friendly garden. And, as these two new books show, we literally have hundreds of choices of garden-worthy native plants to start our journey.